You've successfully copied this link.

How Chinese enclaves became cultural hubs in Australia

From a haven for new migrants to an attraction for tourists, Chinatowns are now a cosmopolitan bridge between Australia and Asia

Chinatowns exist in most Australian states and territories, especially in cosmopolitan capital cities. They have a strong Chinese cultural identity and maintain a strong relationship with China. Many large present-day Chinatowns in Australia came about out of smaller historical Chinese settlements in Australia dating back to the 19th century. Most of the Chinese first immigrated to Australia in large waves during the Australian gold rushes (during the 1850s). In more recent years, Chinatowns have sprawled to include other Asian communes such as Thai, Korean, Indian and Vietnamese.

Where are the Chinatowns in Australia?

There are three major Chinatowns in Australia, located in Sydney, Melbourne and Adelaide, all of which are situated close to or in the city centre. Noted for having a plethora of restaurants, shops and late-night eateries, Chinatowns have turned into a ‘must-visit’ activity for many tourists.

1. Sydney: The largest Chinatown

Sydney’s Chinatown is Australia’s largest and is defined by its distinctly oriental architecture, streetlamps and archways. In recent years, it has expanded and developed in both space and popularity and today, this Chinese-themed urban reserve has morphed into a vibrant powerhouse of Asian-Australian urban modernity and consumer culture.

Chinatown originated from a timber storage yard on Dixon Street in Haymarket in the 1920s. When the government imposed The White Australia policy in 1901, Chinese associations and businesses began settling here and started to sell produce in the nearby Hay Street and opened shops, restaurants and lodgings to cater for the Chinese community.

After the policy was abolished in the 1970s, Chinatown soon transformed itself into an icon of multiculturalism and a tourist attraction. Ceremonial archways were erected at both ends of Dixon Street while lanterns, pagodas and stone lions adorned street corners.

The influx of tourists also saw more migrants and students from other Asian countries, such as Thailand, Indonesia, Korea and Taiwan, settling in the area and establishing businesses. As a result, the boundaries of Chinatown soon expanded beyond Dixon Street to include the broader Haymarket precinct and beyond.

Every Friday from 4pm, the main strip of Chinatown along Dixon Street transforms into a vibrant night market selling Asian street food, desserts and gifts. A common night out in Chinatown can easily include dinner in a Japanese tapas restaurant, followed by a Hainanese coffee-flavoured gelato made with liquid nitrogen.

Chinatown’s population has grown significantly, and tall apartment blocks have emerged, including World Square and Market City, to house many international students who form the area’s main residents.

Real estate: Sydney’s Chinatown

Sydney’s Chinatown has emerged as a hub for real estate services and one of the most popular locations for property investment in Sydney for local and offshore Chinese buyers. Chinatown is also an important residential space for many Chinese migrants.

The 2019 Development Capacity Study on the city of Sydney reports that the three villages with the highest amount of capacity and development activity are CBD and Harbour, Chinatown and CBD South, and the Green Square and City South villages. The village area is characterised by high-rise office towers and residential buildings with future development delivering both new dwellings and non-residential floor space set to continue.1

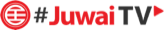

Here are some stats from Juwai.com based on Chinese enquiries on properties in Sydney:

Price range of units:

- Between USD500K – USD750K (30% interest)

- Between USD250K – USD500K (27.1% interest)

- Between USD50K – USD250K (13.9% interest)

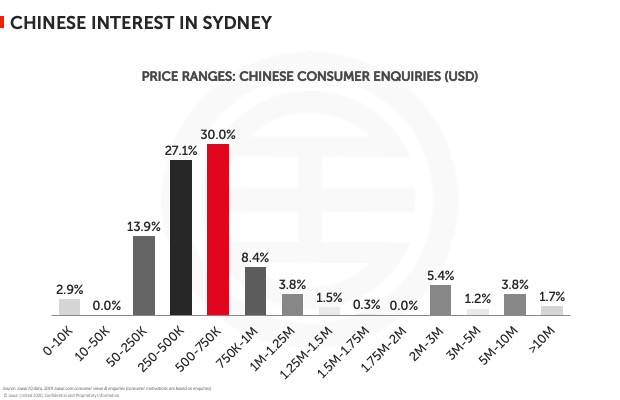

Property types: Residential units with 1-4 bedrooms are the most popular.

2. Melbourne: The oldest Chinatown

If the bright neon signs and hanging lanterns don't give it away, the golden-roofed gateways will. Melbourne's Chinatown is a hub for the local Chinese community. Not only is this the longest continuous Chinese settlement in the Western World, but it is one of the oldest Chinatowns in the Southern Hemisphere. Melbourne’s Chinatown stretches from Little Bourke Street to Lonsdale Street, and within it are an abundance of bars, cafes and restaurants.

It was the discovery of gold in Victoria that drew many immigrants from China who settled in Little Bourke Street and set up businesses that supported those who were digging the goldfields. Since then, Chinatown has become an important source of socio-economic growth for the Chinese community in Melbourne. It not only serves as the bustling heart of Melbourne’s Central Business District (CBD), it is also home to a number of unique assets including the Chinese Mission Church and the Chinese Museum (itself housing the Dragon Gallery which contains a display of the longest dragon in the world).

Club rooms and lodges that once lined alleys in the 1800s have now been replaced with colourful souvenir shops, traditional Chinese apothecaries and restaurants that offer exciting culinary options from many Asian countries. On the third Friday of every month, the Chinatown Night Market takes place, and Heffernan Lane comes alive with pop-up stalls selling everything from dumplings to souvenirs.

Real estate: Melbourne CBD

Most of the 130,000-odd thousand people who live in Melbourne’s CBD are aged between 15 and 34 and living in single-person households or as couples without children. According to Census data, a high number of students (both domestic and international) reside in the area. Immigration from China and India accounted for 32 per cent of overall growth in population numbers.2 As a result, there is much more property development activity in Melbourne CBD than anywhere else in the larger metropolitan area, with most of these developments comprising of high-density high-rise apartment buildings.

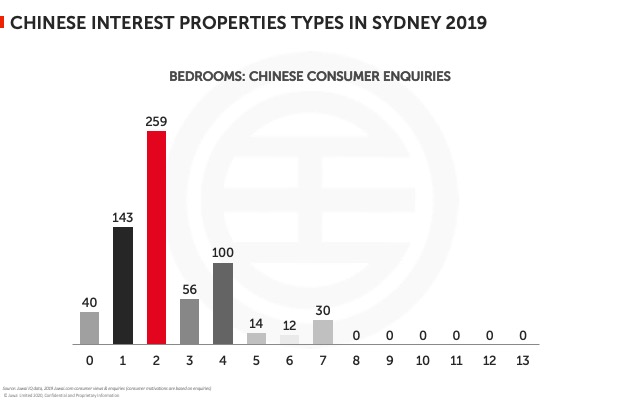

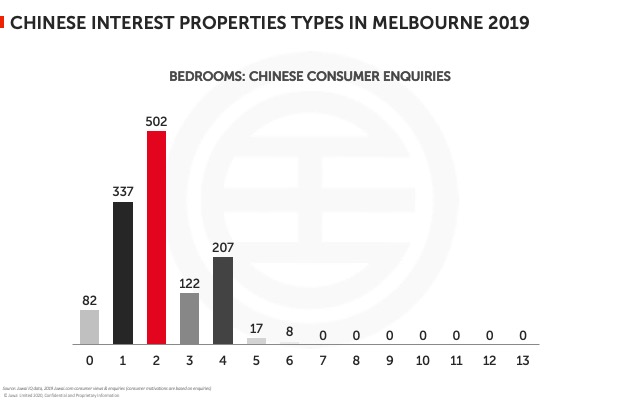

Here are some stats from Juwai.com based on Chinese enquiries on properties in Melbourne:

Price range of units

- Between USD500K – USD750K (17.8% interest)

- Between USD250K – USD500K (67.2% interest)

- Between USD50K – USD250K (3.9% interest)

Property types: Residential units with 1-4 bedrooms are the most popular.

3. Adelaide: The modest but thriving Chinatown

Adelaide has a Chinatown? Yes, it does. It’s on Moonta Street, within Adelaide’s Central Market precinct, and is flanked by Gouger and Grote Streets. Although not as big when compared to Chinatowns in Sydney and Melbourne, this vibrant part of Adelaide brings another part of the world to the city, offering tasty morsels of food and mesmerizing cultural experience.

The first dozen Chinese labourers arrived from Singapore in Adelaide in 1847 to work as indentured shepherds. Many Chinese people disembarked in the port towns of South Australia before traveling overland to the Victorian goldfields. After Victoria enforced its immigration restrictions, many Chinese migrants fled to South Australia. It was then that Adelaide’s Chinatown really began to take shape.

After the White Australian policy was abolished in the 1970s, Chinatown began to boom. It also saw an influx of Vietnamese immigrants. Produce was sold at the Central Market by market gardeners and Asian food shops and cafés began to sprout in the area.

Like Sydney’s Chinatown, Paifang - a type of traditional Chinese archway - welcomes visitors at the opposite entrances of Moonta street. Each entrance is guarded by a Chinese lion statue donated by the Chinese government. The northern archway sign says "Chinatown", while the southern end is marked “The Zhonghua Gate".

With impressive gates, red lanterns, pagoda-style roofs, a maze of oriental-style and award-winning restaurants and shops, Chinatown is a slice of Asia right in the heart of Adelaide and represents a broad cross section of the city’s multicultural community.

Real estate: Adelaide CBD

Adelaide is a magnet for singles who crave urban pace more than suburban space. Most CBD locals are young students and professionals who love the convenience of urban life. A huge variety of houses and apartments keeps young, city-savvy residents feeling right at home.3

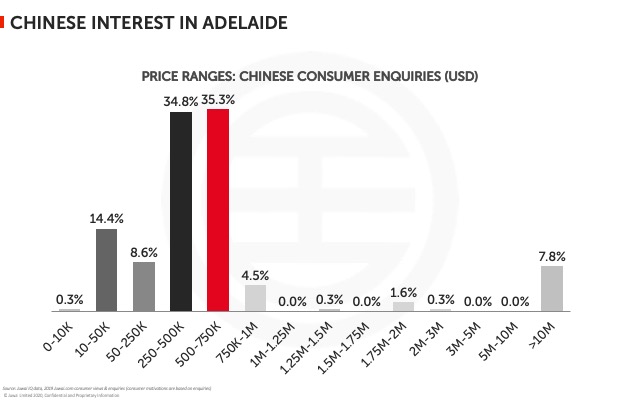

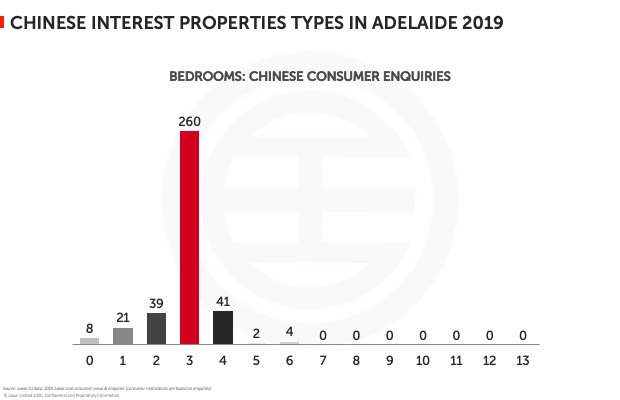

Here are some stats from Juwai.com based on Chinese enquiries on properties in Adelaide:

Price range of units

- Between USD500K – USD750K (35.3% interest)

- Between USD250K – USD500K (34.8% interest)

- Between USD50K – USD250K (8.6% interest)

- Between USD20K – USD50K (14.4% interest )

Property types: Residential units with 1-3 bedrooms are most popular.

Chinatowns today

Over the past 20 years, the number of residents in Australia’s Chinatowns has increased manifold, especially in Sydney. This has helped revitalise these enclaves from ethnic ghettos into vibrant tourist attractions. The influx of tourists also brought a growing number of migrants from other Asian countries apart from China. As such, Chinatowns in Australia have become more multicultural and transnational, incorporating elements of many Asian cultures.

In addition to strengthening economic links between Asia and Australia, these developments have also created a thriving hyperlocal economy. Most Chinatown businesses are small enterprises, including restaurants, beverage shops and fashion brands that take their cues from trends in Asian cities. This exchange has transformed Chinatown into a bridge between Australia and Asia.